Making Is Thinking: Jonathan Boyd’s ethos for the Jewellery & Metal MA at the Royal College of Art

NEWS: Making Is Thinking: Jonathan Boyd’s ethos for the Jewellery & Metal MA at the Royal College of Art

Reading Time:

1 min {{readingTime}} mins

We don’t always make choices that we can articulate through words, so the things we choose to keep close to us offer a murkier, poetic analysis. Through jewellery making and metalwork, Royal College of Art Head of Programme Dr. Jonathan Boyd considers jewellery as a means to explore our immaterial relationship with material objects. As a result, the act of making becomes the process through which we pull things apart and ask ourselves, “Why are we attracted to things and how are things attracted to us?”

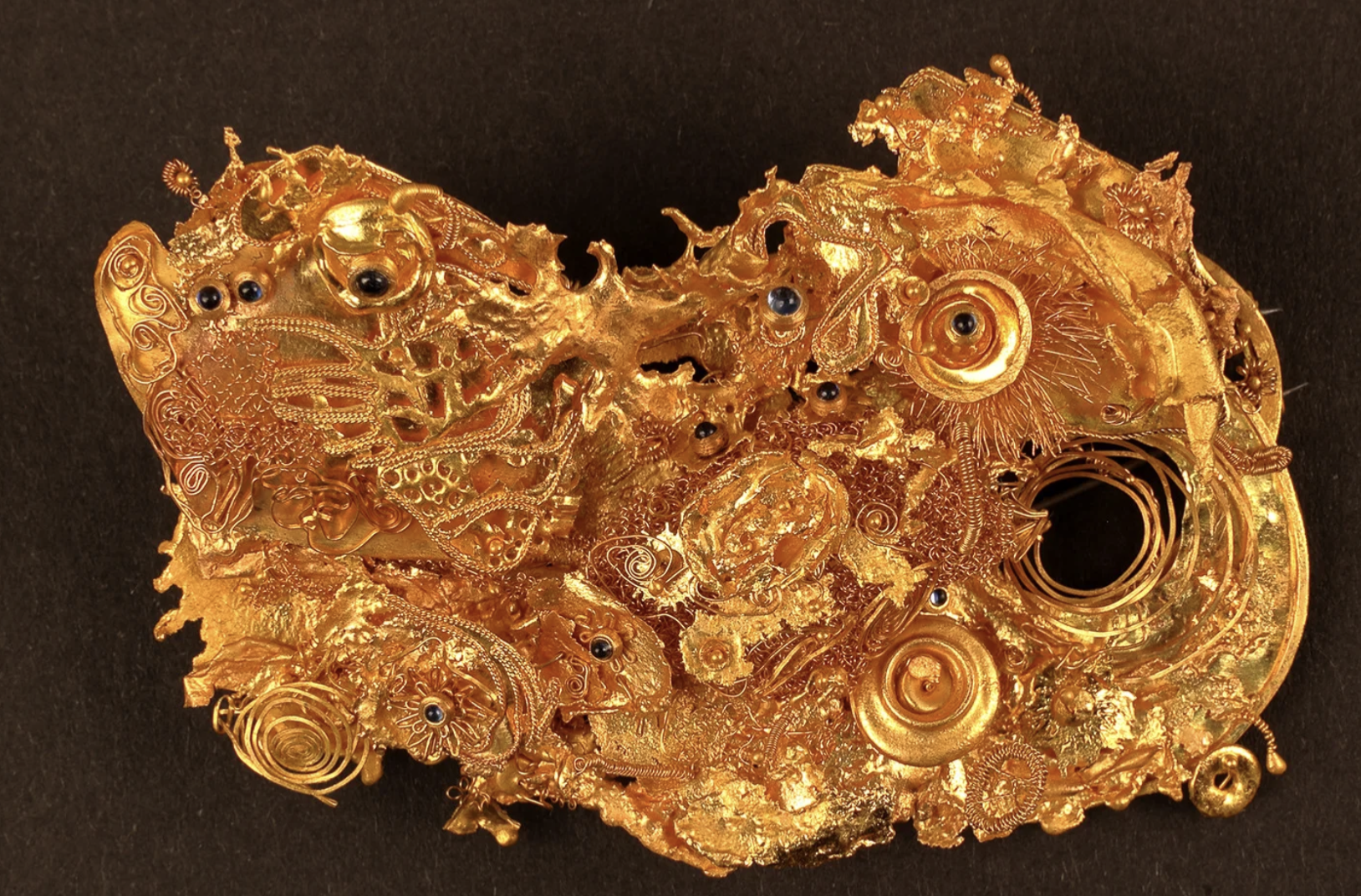

Elaheh Naghi Ganji (2023)

Boyd is originally from Aberdeen and has spent the majority of his life in Glasgow. As a multi-award-winning artist, jeweller and academic, his works have included a variety of materials, specialising in conceptual and narrative-led artworks. You can find some of his pieces in public and private collections, both locally at the Victoria and Albert Museum and internationally at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts (USA). Having previously been a lecturer at the Glasgow School of Art for nine years, Boyd is now the Head of Programme for Jewellery & Metal MA (JaM) at the Royal College of Art. He is represented by Gallery Marzee in The Netherlands.

NG: I came across a quote of yours that said, “Jewellery is on us, remains with us, and changes with us”. Could you elaborate more on the relationship between jewellery and emotion?

JB: While jewellery is an absolutely fascinating subject, I think it’s probably one of the least theorised of all the art disciplines. We have such an emotionally strong connective bond to jewellery, which makes it more than just a frivolous object that we carry with us. If you look at data about what people rescue from housefires, jewellery and weirdly hair combs are always at the top of the list. You live your whole life with these objects, and they become an integral part of you, forming a strange symbiotic bond. Jewellery often re-presents stories or holds deeply personal meanings. The problem with a solely aesthetic understanding of jewellery is that it

Dr. Jonathan Boyd

removes that subjective, emotional, and affective experience. I’m drawn to these sorts of unknown quantities within objects.

NG: Is there a specific project from your career that highlights this dynamic quality of jewellery and metal making?

JB: All of my work situates itself inside the relationship between language and meaning, language and the body, and language and thought. In 2019, I had a solo show at Gallery SO titled ‘Thoughts Between the Land and the Sea: Raising the Doggerland’. It explored jewellery as a means of political storytelling, where I used jewellery as a narrative device for exploring post-Brexit narratives of belonging, being and becoming. It served as an analysis during a time when language was going through this post-truth phase where people were using words in a highly deceptive and confusing manner. All jewellery is socio-political in some way, even if it's very gentle. You wear something and it says something; it means something.

NG: One of the key aims of the Royal College of Art (RCA) Jewellery and Metal MA (JaM) is to “unravel our complex relationship with the material world”. How are students supported within the programme to embark on this exploration?

JB: Tutorials and discussions are key components of our education. The discussions are where we really dig into how you're thinking, why you're thinking, and what those thoughts matter in relation to your overarching artistic practice. We also organise lectures from professionals with different backgrounds – artists, jewellers, philosophers, anthropologists, historians. We invite people who look at these ideas of intangible or material relationships from different perspectives, which are fundamental to the development of a creative, critical practice.

We also aim to facilitate a vivid studio culture. You end up working with students from all around the world, with different ages, backgrounds, and experiences. And being next to people who are asking you questions that you never even thought to ask yourself is enormously eye-opening. As an academic working with such a diverse group of students, I’m constantly forced to re-address the way I think. I see this as a really powerful tool for development; it’s a real privilege.

Kexin Liu (2022)

NG: The JaM programme falls under the Applied Art banner within the RCA. What are some of the multi-directional opportunities that students can take up through their studies?

JB: The MA is founded on independence. Students have access to a variety of specialised facilities, allowing them to create their own methodologies and choose the specific technical resources they want to use. Some of our students have started exploring things like AI or motion capture, which we view as offering other ways of thinking about the body or the self. We encourage students to try and find their own path to develop the right tools, always with the support of academic expertise.

While the programme is distinct, there’s also a lot of collaboration and crossover with the Ceramics & Glass MA. We give students the space to think about material processes, for thinking through making, and thinking through the materials. It’s this breadth of what we do that I find really exciting. We like to make stuff, but making is thinking; it’s a way of processing and reflecting on the world.

NG: This variety of perspectives is also heavily reflected through the different voices of the academic and technical staff that make up your department.

JB: Definitely. We’re in a really fortunate position, as all the staff in the programme are practising artists, designers and researchers. Starting with myself, I’ve had two solo shows in the past five years, and there’ll be another one next year. Our senior tutor Katharina Vones is a practising researcher, who has just been up in Orkney doing a massive project on beach waste and renewables. Professor Michael Rowe is the key figure in postmodern applied arts in terms of metal; he invented postmodern silversmithing. We have some internationally renowned silversmiths, with the likes of Rebecca de Quin, Max Warren, and Adi Toch.

Mah Rana is a world-famous jeweller but now, she’s also just finishing a psychology PhD around making and cognitionI would say Mah’s approach is fundamental to the way we think as a programme, which is very interdisciplinary. Our home is jewellery and metal, but what we really want is for people to come at these conversations from new angles. As an academic staff, we all support this type of interdisciplinary thought. As a staff group, one of the things that we're really focused on is developing better ways of talking about our research to each other. The RCA is founded on peer learning, both amongst students and staff alike.

The technical staff also consists of a strong group of internationally renowned makers. We’ve just co-exhibited with the research group FOLD(s) in China with new RCA members including Adam Henderson, who is one of our technical staff. We’ve got renowned silversmiths like Pete Musson and Mary Ann Simmons, who both have objects in major international and national collections.

Huimin Zhang (2023)

NG: In the next few weeks, the current Jewellery and Metal students will be showcasing their work as part of the RCA2025 exhibitions. What can we expect to see from this year’s event?

JB: There’s a huge diversity of approaches to the things that really matter to jewellery – understandings of the self, of the body, of design, of art, of our relationship to the material world. One of the key aspects is how students tell stories through making and the objects they create. Some students are investigating what it means to be a person, whether it’s the deeply intimate relationship with oneself, or else the sustainable and ethical implications of a connection with nature. There has also been a big rise in students working in digital processes like artificial intelligence, who are really trying to explore what intelligence is in the first place.

NG: Can you mention some graduates whose work has really stood out to you this year?

JB: AeRi Go is doing some interesting metal-based work exploring the artistic potential of hidden spaces. Alex Kinsey is looking into class identities and thinking about how they represent personal narratives. Anastasiia Riabokon is making some stunning work using different types of stones. Bocen Zhou is experimenting with glass as a medium for recreating moving parts within an object. The thing that is most exciting is that none of the work looks the same, which I think is always the best way of telling how students are supported in driving personal approaches.

NG: Now that these students are reaching the end of their time at the RCA, what are you hoping that they leave with as they enter the next phase of their artistic journeys?

JB: Our goal is that students leave with an artistic practice, which they have developed themselves with the support of academic and technical staff, that can be adaptable for the rest of their careers. That they can take these different ways of understanding, methodologies and approaches, to then mould them to suit their needs as their artistry continues to develop. The approach that we hope they leave with is one that is self-critical, reflective and reflexive.

We’re currently seeing a wide range of outputs from former graduates. Within the fine arts, Jasleen Kaur, who graduated 14 years ago, has just won the Turner Prize. There’s also Lili Murphy-Johnson, who graduated a couple of years ago and was a Bloomsbury Award nominee. Then you have people working in applied art, starting exhibitions across the world. We have several students in China who are establishing their own design hubs and applied arts studios. There are also students working in design. The common thread running through all these different paths is that they have all developed a type of independent critical approach to their work.

Lili Murphy Johnson (2023)

NG: Speaking directly to people who may be interested in applying to the JaM programme for the next academic year – is there anything in particular that you look out for in portfolios and application submissions?

JB: We are looking for two main things. On a conceptual level, we want to see evidence of your own artistic voice. How do you communicate the way that you see the world? Is it through objects, drawing, or making things? We want to see your ability to visually and materially analyse the world as you see it. Whatever the medium, how do you make and think through making?

On a more practical level, we want to see really good pictures of your work. We don’t need to see portfolios with loads of arrows, notes, or processes – focus on submitting good photos. Show us the work that you made and why it’s special. To support this, when you’re talking about your work, we want to know three things – why you do it, what it means to you, and why you think now is the time to embark on your postgraduate study.

As told to Nicholas Gambin, current student on the Writing MA at the RCA.

- Visit the Jewellery & Metal MA graduate exhibition, RCA2025, from 19-22 June.

- Applications for the September 2025 intake of the Jewellery & Metal MA are open until 30 June. Applications for the 2026 intake will open this September.

- If you're interested in joining the Technical Services team for Applied Arts, view vacancies or register for notifications on the RCA jobs website.

This article was sponsored by the RCA

To read more on the RCA click here:

Jewellery and Metal MA Students Showcasing Work At Upcoming Royal College of Art Graduate Exhibition

Author:

Published: